Words Tracey McCallum

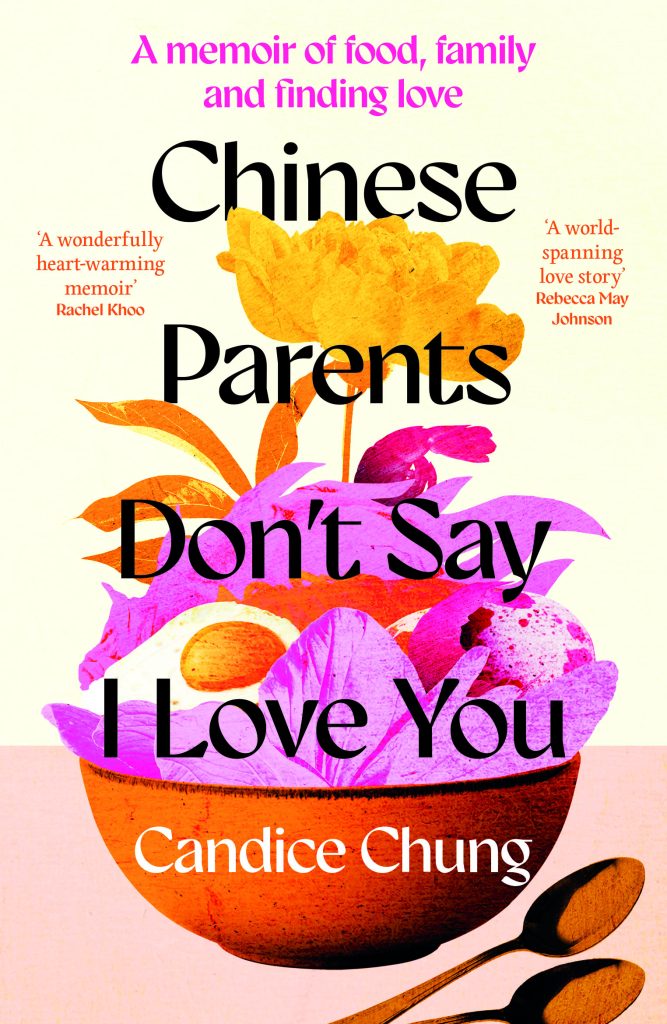

Hailing from Sydney but now based in Glasgow, author, journalist and editor Candice Chung talks to Westender about her first book, Chinese Parents Don’t Say I Love You.

As well as writing and editing, you were a restaurant reviewer. That seems like a dream job — was it as delightful as it sounds?

I’ve always felt it’s a huge delight and privilege to get to write about food in any capacity. One of the best things about that job was discovering how a restaurant or café came to be. My favourite food stories usually begin with a memory or an obsession — the memory of a Korean-born chef’s childhood road trips with their truck-driving father and eating barbecued abalones on the coast, for example. Or one couple’s obsession with made-to-order sandwiches they ate on their honeymoon in Rome, and their attempt to re-create that experience in a tiny inner-city sandwich shop.

These stories of unspoken hopes and desires aren’t necessarily what customers would have access to on an everyday basis, even if they ate somewhere regularly. You can feel it, and it’s what sometimes attracts us to a menu, a style of eating (shared plates / casual / exquisitely formal) or an ambience. As a food journalist, being able to make that connection for myself and for readers is very satisfying.

What inspired you to write Chinese Parents Don’t Say I Love You?

I was at a crossroads in my life. During the pandemic, I found myself having to decide whether to move overseas for a relatively new relationship or to stay behind and be close to my parents. How things unfolded from that point took me by surprise, and I felt compelled to make sense of that choice. There were also some uncanny parallels when it came to major turning points in my and my parents’ lives. The book was a way for me to wrap my head around those too.

How would you pitch the book to Westender readers?

My memoir is about the small intimacies of our eating lives, how food can bring us together, but also sometimes keep us apart. It’s set in a time of my life when I worked as a freelance food reviewer for a Sunday paper in Sydney. My parents, whom I had drifted apart from, became my plus-ones after a long-term relationship came to an end.

About three years into our reviewing gigs together, I met someone new, a geographer from Canada. As is the way of love, it forced the narrator (ie. ‘book-me’) to confront some past hurts and vulnerabilities. That, and a lot of food talk.

What did you learn about your parents through eating together, and how has it changed your relationship?

One thing I learnt was that my parents are much more adventurous than I realised. And because they understood our food outings were part of my work (and they have impeccable work ethics), they were always down for the ride. Pub tacos, Somali lunch, romantic trattoria, hot dogs in the middle of nowhere — you name it, they did it all.

I think getting to spend time together in these ‘third spaces’ — places that were not our homes or part of our quotidian lives — allowed us to access slightly different parts of ourselves. It helped us open up a little, in the same way going on holidays sometimes allows us to get to know each other in surprising ways.

What did you learn about yourself?

This is a huge question. I joke to my editor that the ‘secret thesis’ of my book is to answer why it’s so hard to feel close to people who are the nearest and dearest to us. I see now that 300-odd pages won’t quite get to the bottom of that.

What was the most challenging aspect of writing this memoir?

One of the trickiest things about writing from life is that you want the people in your life to remain in your life after the writing is over. This means the possibility of hurting someone’s feelings and whether you are being emotionally true to everyone involved can weigh heavily on your mind. I found that the most challenging.

A very astute interviewer once asked: ‘If food was a way for your parents to say the unsayable, is it also a way for you to write the unwritable?’ And she was right. Writing about food was a way of thinking about love and longing for me. It gave me the courage to look at my own desires through a kind of buffer.

What would you say are the main differences between Cantonese parenting and Western/European parenting?

We can only know the weirdness of our own family from the inside. It’s quite impossible to compare and contrast in a meaningful way, especially across cultures, when we have so little in terms of field notes.

What I can say is that I love meeting readers from all over the world who come up to me and say, ‘Japanese parents / Scottish Protestant parents / Irish parents / Indian parents / Indonesian parents don’t say I love you, either!’ It leads me to think that cultural differences aside, so many of us have ‘near misses’ when it comes to wanting to feel and express affection with our loved ones.

Why do Chinese parents not say “I love you”?

In 2012, I wrote a story with that exact title for The Sydney Morning Herald. It was based on a viral video in which a group of university students in China were asked to say ‘I love you’ to their parents for the first time and record what happened. At the time, I found it funny because I could picture my Mum and Dad responding similarly — with complete bewilderment.

Years later, when I started writing my memoir and tried to figure out whether words or gestures do a better job when it comes to feeling close to someone, I realised the ‘why’ of not saying ‘I love you’ is perhaps not that important. By asking ‘why’, we imply that saying ‘I love you’ is the gold standard, or that verbal affection should be the norm — and that’s worth interrogating.

What value does communal eating bring to our lives and relationships?

I have a running joke with my sister where we talk about spending ‘quantity time’ (as opposed to quality time) together. Some hangouts are just ordinary — a solid five out of ten. We can’t always have deep, emotional conversations or mind-blowing meals every time we see each other.

But those ordinary moments together are perhaps just as, if not more, important. It’s during those ‘medium times’ that you really get to know someone and catch up on the running arc of each other’s lives. Not having the chance to regularly eat together means we stand to lose some of that.

Describe your ideal dinner scenario — where, who and what would be on the menu?

That depends on who I most miss hanging out with in the moment. Right now, my ideal dinner would be a home-cooked meal with Cantonese soup made by my Mum, at the round marble table in my parents’ inner-city Sydney home, with my family.

Tell us about your favourite West End places:

I’m absolutely obsessed with Amulet for their hand-brewed coffee — I’m convinced they make the best in town. I love Mrs Falafel’s food truck for a delicious, affordable lunch, especially with a swim at the Arlington Baths beforehand. Sushi Riot for life-sustaining nigiri platters, Valhalla’s Goat for natural wine. For dinner: Sylvan’s thoughtful vegetarian small plates, Goat in the Tree for Moroccan, Rafa’s for tacos, Gloriosa, and Corner Shop for special catch-ups.

After living in Glasgow for a few years now, have you discovered any favourite traditional Scottish foods?

I grew up eating oats for breakfast, and it’s still my go-to most days — does that count?

One fun fact: I read Scottish chef Pam Brunton’s brilliant memoir Between Two Waters, where she writes about traditional Scottish foods. I realised there’s a version of mince and tatties in Hong Kong — mince and rice. I ate it a lot as a kid but never made the connection. There’s also a Dumbarton Road in Hong Kong, thanks to Scotland’s historical influence. Did you know that?

After a busy year of promoting the book, what’s next for you?

I’m working on new essays and funding applications for the next project. The paperback version of Chinese Parents Don’t Say I Love You is coming out in the UK in spring 2026, along with the Canadian edition. I’m also very honoured and excited to be on the judging panel for the 2026 Kavya Prize’s New Writers’ Award.

Chinese Parents Don’t Say I Love You: A Memoir of Food, Family and Finding Love by Candice Chung (Elliott & Thompson) is published in paperback on 5 February 2026, £10.99, and is currently available in hardback from Waterstones, £16.99. Both are available with a 10% discount at Waterstones Byres Road.