By Mike Findlay

Westender readers would be hard pushed not to notice Brian Toal’s complimentary review of Sarah Smith’s Hear No Evil in the January/February edition of the magazine.

Glasgow-based Sarah Smith has worked previously as a creative writing tutor, family history researcher and project worker with charities, including Deaf Connections, who supported her in the creation of this enticing book.

Sarah Smith was presented a New Writers Award for Fiction from the Scottish Books Trust in 2019; and graduated with an MLitt with distinction for Creative Writing at the University of Glasgow in 2018.

Having discovered newspapers articles from the 19th Century of a landmark case of deaf woman who is accused of throwing her own baby into the River Clyde, she was intrigued to find out more.

Hear No Evil brings to life the story of Jean Campbell in a compelling tale which takes us between Glasgow and Edinburgh and back again, and shows how class, education and attitudes towards people that are deaf informed much of Scotland’s justice system at the time.

At the heart of this book is Jean’s relationship with Robert Kinniburgh, a teacher from the Deaf and Dumb Institute, who works to crack the code of being able to effectively communicate with her.

Reading this book, it’s hard not to reflect on how far our justice system has come in its treatment of some of society’s most vulnerable people, but also how far we have still to go.

What originally inspired you to write the book?

When I was working at Deaf Connections, an organisation in Glasgow whose roots stretch back to 1819, I met local historian and author, Robert J Smith, whose book, The City Silent, mentioned the case and quoted a couple of newspaper articles about it. On a dark winter’s evening, a woman had been seen to throw a baby into the River Clyde from the Old Bridge in Glasgow. It was the first time a deaf person had been tried at the High Court and, the accused, Jean Campbell, seemed such a key figure that I was curious to know more about her.

What process did you go through to research Jean’s story?

I read the court transcripts and contemporary accounts in newspapers and journals but that got frustrating after a while because there was very little that told me who Jean really was or what had led her to commit this crime. There were copious pages written about her but much of it was confusing and contradictory and limited to ‘experts’ views on her deafness and social status. I wanted to get to know Jean and learn about the life of a deaf person living at that time, but the establishment of 1817 treated her more like a laboratory experiment than a real woman. In contrast, Robert Kinniburgh, who interpreted for Jean at her trial was easy to research because he was involved in promoting education for deaf children and his life and work had been recorded.

Any other further research you did for the book?

As well as telling a historical crime story, the book depicts aspects of deaf people’s experience. On that, I got a great deal of help from Lilian Lawson and Ella Leith at Deaf History Scotland, a charity that conserves archives and provides information and events about deaf heritage and culture. Without access to their resources and knowledge, it would have been impossible to write the character of Jean.

How did you manage to accurately depict life in the 1800s?

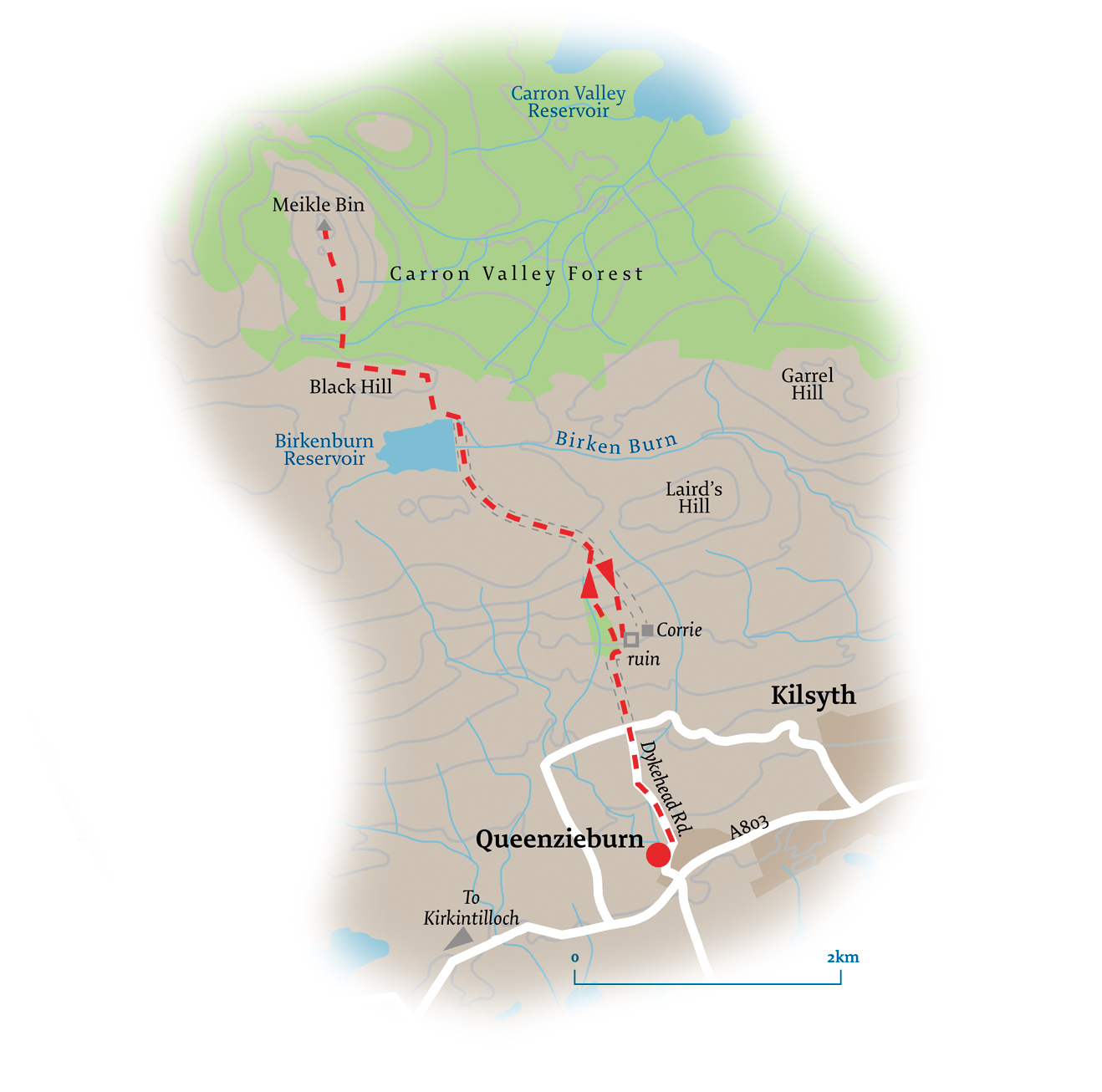

I’d start each writing session by reading a newspaper from 1817. Almost none of what I read made it into the novel but, it put me in the mindset of someone living at the time. I searched for books and websites that gave everyday details; things like how long a coach would have taken to travel between Glasgow and Edinburgh or how a maid would do the household laundry. I walked around the areas in the book with old maps to try to imagine how my characters would inhabit them.

In terms of character development, what did you do to visualise and realise the characters?

Characters are all different. Some are integral to the story but take a long time to come into focus and, occasionally, the odd one pops up unexpectedly. For example, I wrote a lot about what Robert Kinniburgh ‘did’ in the story, long before I was sure what he looked like and what character traits he had. Whereas Martha Sproull, the McDougall’s maid, began as a very minor character but felt fully realised and took on a life of her own as the novel developed.

Reflecting on how Jean was treated at the time, what do you think her treatment would be today in Scotland’s justice system?

Jean would have more rights today because they’re now enshrined in law. British Sign Language (BSL) is recognised as a language, technology has revolutionised the way that we communicate, and an interpreter would be present in interviews and at court as a matter of course. However, there are still lazy assumptions made about deaf people and a lack of resources and infrastructure to fund the support they need. Her treatment would be fairer but not necessarily perfect.

What is the overarching message you want readers to take away from the book?

That listening to people is the key to progress. Things only change when we take the time to see the world from other people’s perspectives.

What was the most enjoyable part of writing the book?

Honestly, I enjoyed most of it! The research, workshopping early drafts, working with my agent and editor, seeing the finished product emerge and appear in bookshops. I even loved the redrafting and editing process.

What was the most challenging?

Without a doubt, describing the deaf experience and sign language as a hearing person. I worried about getting it wrong all the time. I never felt that it was my place to speak for deaf people, they’re much better informed than me! Luckily, there were deaf people who were willing to help me. I hope that the fact that Jean is at the centre of the story rather than a tokenistic minor character is seen as a positive thing.

Anything else you would like to share regarding the book?

The answer to the mystery at the heart of the novel – how Jean and her baby came to be on the Old Bridge in Glasgow – begins to unravel at the McDougall’s house. The locations I used, in Partickhill and down to the river at Partick, are near where I’ve lived for almost thirty years.

What is next for you?

I’m working on a novel that’s set in 1920. It’s about the impact of WW1 on a woman working in a back-court picture house. Glasgow was then on the brink of becoming known as Cinema City, with more per person than anywhere else in the UK. It’s another fascinating story to research.

Anyone wanting to purchase a copy of ‘Hear No Evil’ by Sarah Smith can do so online at: https://www.tworoadsbooks.com/titles/sarah-smith-3/hear-no-evil/9781529369120/

Return to Culture and Arts